It may sound puzzling and unusual to ask about the associations between criminal behavior and number of children one has. But in fact, it does not have to be so for evolutionary social scientists. Evolutionary psychologists and human behavioral ecologists could assume that criminal behavior is an adaptive trait. These kinds of explanations are called ultimate because they rely on evolutionary processes like natural selection. More precisely, criminal behavior can be analyzed using the evolutionary biological conceptual framework labeled as Life History Theory. This framework assumes that individuals that live in “harsh” ecologies have specific pattern of adaptation which reflects on reproductive success as well (ecological harshness encompasses various environmental characteristics that increase mortality in a given population, e.g., poverty, stress, deprivation, hostility, pathogen load, etc.). Hence, natural selection in harsh environments may favorize individuals with earlier start of reproductive phase and earlier first reproduction, and having more offspring with diminished parental investment despite the possibility that this reproductive pattern is also related to shorter lifespan. Logic of the theory is apparent: in harsh environment it is not adaptive to delay reproduction because individuals risk death without producing offspring; furthermore, individuals cannot invest in offspring because these ecologies lack resources and therefore, the adaptation is heavily relied on offspring quantity. This reproductive pattern is called “fast” while the opposite pattern represents “slow” life history: delayed first reproduction, fewer offspring with elevated parental care, and higher longevity. Indeed, various empirical research in humans confirm this hypothesis: environmental conditions like lower socio-economic status, diminished housing quality, deprived environments, and dysfunctional families in childhood predict earlier first reproduction and higher number of children. Behavioral characteristics associated with fast life history belong to the fast Pace Of Life (POL); typical fast POL behaviors are aggressiveness, impulsiveness, and boldness. Individuals who express criminal behavior indeed more frequently originate from harsh environments characterized by poverty and dysfunctional family relations, and they are also characterized by personality traits like impulsivity and aggressiveness. Therefore, it is not surprising that some authors assumed that criminal behavior is associated with fast life history as well. There are some empirical data that confirm this hypothesis: the findings from Sweden’s total population (N=4849478) show positive association between criminal offending and fertility (number of children); furthermore, higher number of lawful sentences positively predicted reproductive success. Hence, within this theoretical framework, criminal behavior may be adaptive (in an evolutionary-biological sense) because it enables higher fertility.

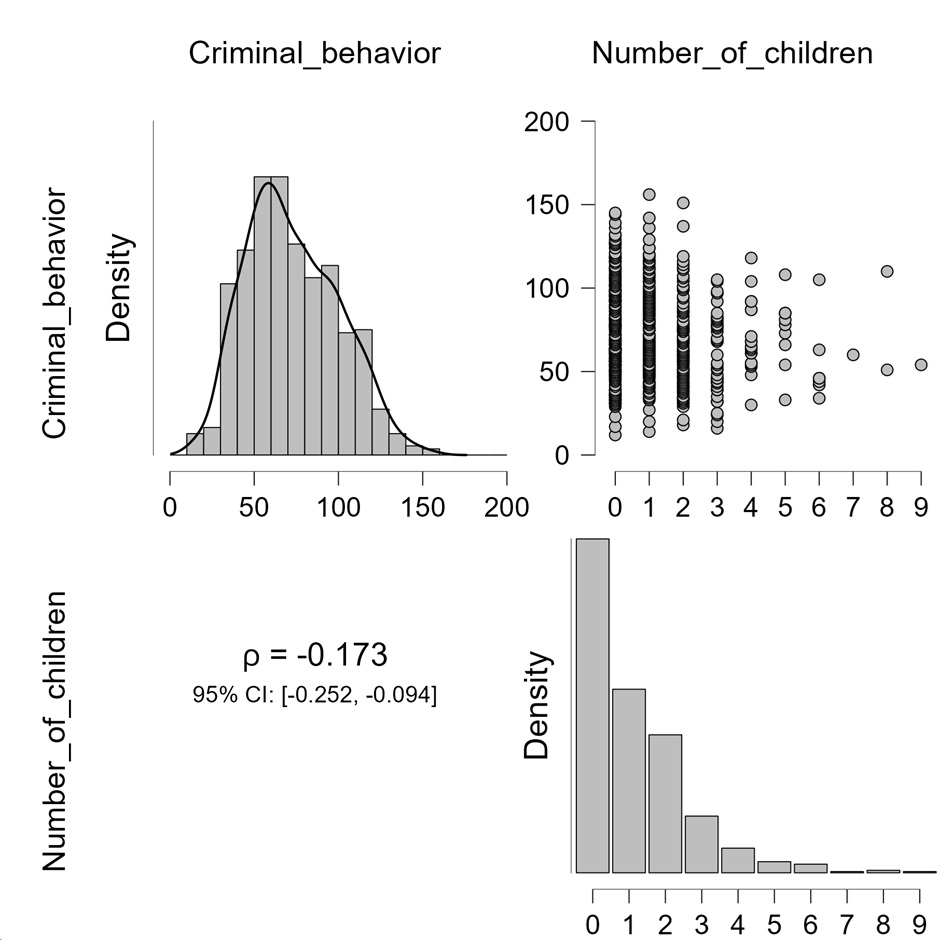

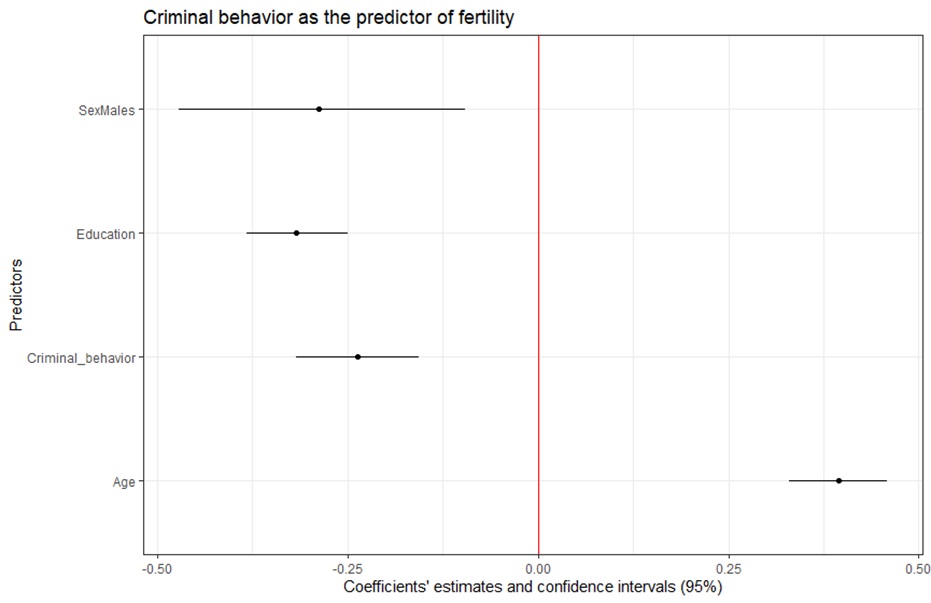

We tested this intriguing hypothesis using the data collected on the PrisonLIFE project. We conducted the analyses on the sample of 618 prisoners who were serving their sentences in several major prisons in Serbia (14.60% of female participants; Mage=39.75 years |SD=10.28|). The association between number of children and criminal behavior was the key target of our analysis. Criminal behavior was operationalized via total score on the Offender Assessment System-based protocol (OAS) – it is an assessment of reoffending conducted for every prisoner by the penitentiary facility staff. OAS represents very comprehensive operationalization of criminal behavior because it encompasses various indicators like characteristics of criminal offending, personal history of criminal behavior, attitude toward offence, substance abuse, socially-destructive behavior and others. If we take a look at the correlation between criminal behavior and number of children (Sperman’s coefficient of rank correlation was calculated because number of children is by definition a rank variable) we can observe small but statistically significant negative association (Figure 1). In order to provide stricter test of this association, we fitted Poisson’s regression with number of children as a criterion measure while criminal behavior, together with participants’ sex, age, and education were analyzed as the predictors (Figure 2). Once again, criminal behavior was significant predictor of fertility with a negative contribution to the prediction. Beside criminal behavior, significant predictors were age (positive) and education (negative); females reported higher average fertility than males as well. Analyzed predictors explained 36% of fertility’s variation in this model.

Figure 1. Correlation between criminal behavior and fertility

Figure 2. Poisson’s regression for the prediction of variation in fertility

Hence, our findings not only did not confirm the Life History-derived hypothesis – they are opposed to it. How can we explain the obtained association between criminal offending and fertility? In regard to ultimate explanations, firstly we must note the complexity of analyzed phenomena, both regarding to biological processes and physical and social environment. Every theory has its domain of application and this stands for Life History as well: it is possible that the link between harsh environment and reproductive outcomes is not relatively simple as assumed by this theory and that it depends from various characteristics of organisms and their socio-ecologies. Reproduction of contemporary humans is plastic, flexible, and partially intentional and consciously controlled; simple reproductive patterns labeled as “fast” and “slow” described by prototypical form of Life History Theory probably cannot even be found in contemporary human populations. Furthermore, Life History Theory is not the only evolutionary conceptual framework that attempts to explain the association between harsh environment and reproduction. For example, the “silver spoon” hypothesis is in contrast with Life History prediction: harsh environment may inflict negative consequences on somatic state of individuals, impairing physical (and perhaps mental) health, which consequently may reflect on fertility as well.

Our data may be incongruent with Life History Theory but they are in line with many proximate explanations of the link between criminal behavior and fertility (proximate explanations are not based on evolutionary processes; they are focused on relatively “closer” causal determinants of a phenomenon – in case of human behavior these could be physiological and morphological traits, developmental pathways, or environmental characteristics). Namely, various scholars empirically detected negative association between fertility and criminal offending or similar behavioral patterns like antisocial personality disorder. This finding can be explained by substance abuse or unemployment – they both also negatively correlate with fertility (individuals often tend to achieve certain socio-economic status and intended level of salary before they have children, which is contrary to Life History Theory predictions). Finally, we should observe the following as well: our current data, similarly to many other (fortunately, not all) are based on cross-sectional design – the data on both criminal behavior and fertility are collected simultaneously. Hence, we cannot make conclusions about the causal links between explored variables: we cannot say whether criminal behavior causes lower fertility or it is vice versa. Furthermore, the latter causal direction is indeed plausible – there is data showing that starting a family and becoming a parent can help individuals to desist from crime. Leaning on these data scholars sometimes explicitly state that if states aspire to elevate fertility, one of the processes that can facilitate this is crime reduction and prevention. Finally, what this interesting association between criminal behavior and fertility can say to us, as evolutionary social scientists? We should always keep in mind that humans are very complex beings, both biologically and socially, and we should not overlook proximate causes of behavior – in fact, our research should aim to integrate ultimate and proximate process, and thus, lead to more comprehensive insight into human behavior.

Janko Međedović

References

Abell, L. (2018). Exploring the transition to parenthood as a pathway to desistance. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 4, 395-426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-018-0089-6

Basto-Pereira, M., Gouveia-Pereira, M., Pereira, C. R., Barrett, E. L., Lawler, S., Newton, N., … & Sakulku, J. (2022). The global impact of adverse childhood experiences on criminal behavior: A cross-continental study. Child abuse & neglect, 124, 105459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105459

Del Giudice, M., Gangestad, S. W., & Kaplan, H. S. (2015). Life history theory and evolutionary psychology. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The handbook of evolutionary psychology – Vol 1: Foundations (2nd ed., pp. 88–114). Wiley.

Ganser, B., Guzzo, K.B. (2023). Criminal offending trajectories during the transition to adulthood and subsequent fertility. In: Schoen, R. (eds) The Demography of Transforming Families. The Springer Series on Demographic Methods and Population Analysis, 56, (pp. 255-278). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29666-6_12

Hayward, A. D., Rickard, I. J., & Lummaa, V. (2013). Influence of early-life nutrition on mortality and reproductive success during a subsequent famine in a preindustrial population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(34), 13886-13891. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1301817110

Huang, T., Chiang, T. F., & Pan, J. N. (2015). Fertility and crime: Evidence from spatial analysis of Taiwan. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36, 319-327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9440-9

Jacobson, N. C. (2016). Current evolutionary adaptiveness of psychiatric disorders: Fertility rates, parent−child relationship quality, and psychiatric disorders across the lifespan. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 824–839. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000185

Jarjoura, G. R., Triplett, R. A., & Brinker, G. P. (2002). Growing up poor: Examining the link between persistent childhood poverty and delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18, 159-187. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015206715838

Jones, S. E., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2011). Personality, antisocial behavior, and aggression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(4), 329-337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.03.004

Kwiek, M., & Piotrowski, P. (2020). Do criminals live faster than soldiers and firefighters? A comparison of biodemographic and psychosocial dimensions of life history theory. Human nature, 31(3), 272-295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-020-09374-5

Lawson, D.W. (2011). Life History Theory and human reproductive behaviour. In: Swami, V. (ed.). Evolutionary Psychology: A Critical Introduction (pp. 183−214). Wiley-Blackwell.

Međedović, J. (2020). On the incongruence between psychometric and psychosocial-biodemographic measures of life history. Human Nature, 31(3), 341-360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-020-09377-2

Međedović, J. (2023). Evolutionary Behavioral Ecology and Psychopathy. Springer Nature.

Međedović, J. (2023a). Pace-of-Life Syndrome (POLS). In: Shackelford, T.K. (eds) Encyclopedia of Sexual Psychology and Behavior (pp. 1-5). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_1677-1

Ministarstvo Pravde: Uprava za izvršenje krivičnih sankcija. (2013). Priručnik za primenu Instrumenta za procenu rizika do i tri godine. Ministarstvo Pravde, Republika Srbija.

Ministarstvo Pravde: Uprava za izvršenje krivičnih sankcija. (2013a). Priručnik za primenu instrumenta za procenu rizika preko tri godine. Ministarstvo Pravde, Republika Srbija.

Vujičić, N., & Karić, T. (2020). Procena rizika i napredovanje u tretmanu u Kazneno-popravnom zavodu u Sremskoj Mitrovici. Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu, 68(1), 164-185. https://doi.org/10.5937/AnaliPFB2001170V

Yao, S., Långström, N., Temrin, H., & Walum, H. (2014). Criminal offending as part of an alternative reproductive strategy: Investigating evolutionary hypotheses using Swedish total population data. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35(6), 481-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.06.007